'American Epic' Filmmakers Tell America’s Untold Musical Story

Posted on May 10, 2017 by Lindsey Foat

When director Bernard MacMahon and producer Allison McGourty started research on the upcoming PBS documentary series American Epic, Robert Redford gave them a piece of advice.

“Bob said, ‘Don’t stress about finding the story with your filmmaking because the story will find you,’” McGourty said.

American Epic is the largely forgotten story of the first electrical sound recording machine and the diverse range of folk musicians it captured in the 1920s. From records featuring Blues guitarists in the Mississippi Delta to Hopi Indian Chanters, the filmmakers characterize this period as “the first time America heard itself.”

Letting the story find them was a tall order as little documentation from this era was known and 90 percent of the recordings were destroyed. But through extensive research, restoration of hundreds of recordings, thousands of photos, and hours of film — plus sheer luck — the team behind American Epic has captured the era that forever altered American music and culture.

“It’s the story of one of the great moments in American history – when the voices of working people, minorities, and rural people throughout the country were first heard,” MacMahon wrote on the film’s website. “It celebrates all I admire about the country – its rich culture, technological innovation, entrepreneurism and its freedom of speech.”

To tell the stories of these everyday Americans, MacMahon and McGourty traveled across the country, often to small towns, to track down the descendants of the original musicians. As luck would have it, they also encountered an engineer working to reassemble the recording system from original parts — now the only one left in the world.

“Bob said, ‘Don’t stress about finding the story with your filmmaking because the story will find you,’” McGourty said.

American Epic is the largely forgotten story of the first electrical sound recording machine and the diverse range of folk musicians it captured in the 1920s. From records featuring Blues guitarists in the Mississippi Delta to Hopi Indian Chanters, the filmmakers characterize this period as “the first time America heard itself.”

Letting the story find them was a tall order as little documentation from this era was known and 90 percent of the recordings were destroyed. But through extensive research, restoration of hundreds of recordings, thousands of photos, and hours of film — plus sheer luck — the team behind American Epic has captured the era that forever altered American music and culture.

“It’s the story of one of the great moments in American history – when the voices of working people, minorities, and rural people throughout the country were first heard,” MacMahon wrote on the film’s website. “It celebrates all I admire about the country – its rich culture, technological innovation, entrepreneurism and its freedom of speech.”

To tell the stories of these everyday Americans, MacMahon and McGourty traveled across the country, often to small towns, to track down the descendants of the original musicians. As luck would have it, they also encountered an engineer working to reassemble the recording system from original parts — now the only one left in the world.

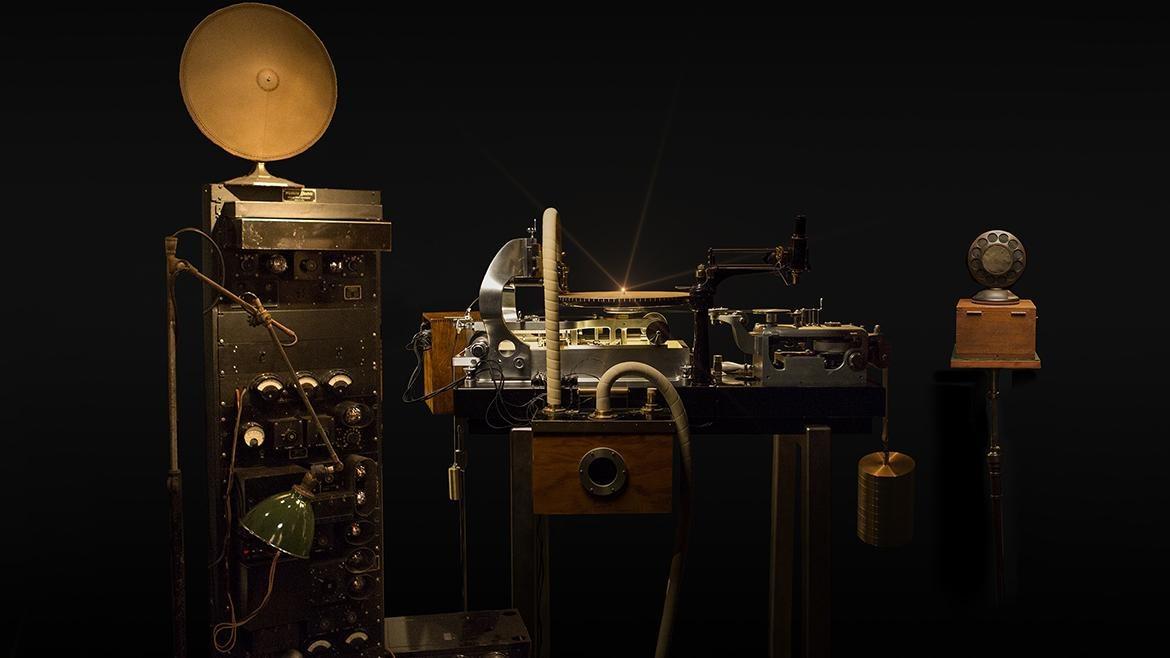

The restored Western Electric Recording System: Western Electric Recording Rack, Scully Lathe, and Western Electric Microphon

Lo-‐Max Records, Ltd.

Along with Robert Redford, musicians Jack White and T Bone Burnett served as executive producers on the multi-part series, which includes performances of the music from the era recorded on the reconstructed machine from contemporary artists like The Americans and Jerron “Blind Boy” Paxton.

McGourty and MacMahon came to Lawrence, Kansas, to screen part of American Epic at the Free State Festival last summer. See a video excerpt from their panel discussion after the screening here. After the event KCPT talked with them about their filmmaking odyssey. Their responses have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

American Epic goes so far beyond a documentary series. The body of work that you’re creating also includes a book, contemporary recording sessions and a digital archive with the research and restored materials. What do call what you’ve created since it’s so far beyond just filmmaking?

BM: I think that’s why it’s called American Epic. (Laughs) Because once we started getting into the meat of the production, we realized it extended into so many other areas. And I think there’s a duty if you find this material to preserve it and protect. And to also preserve all the other stories you don’t have the opportunity to tell to make sure they’re documented and that that material is archived properly… There was almost like a football league table approach in how the 100 artists were chosen to make 10 [that are featured in the series.] But we realized early on that this material was really valuable even if this particular artist wasn’t going to make it into the film. Their interviews, the family’s interviews, the photographs those should be available. So that’s where the box set comes in with the hundred songs on it, because that’s like a cue for people to explore the thousands of things that are out there from that era.

AM: It was really to do justice to the people themselves and the families, because for example when we found photos of Mississippi John Hurt or [the Tejano musician] Lydia Mendoza you want the public now to see them as they were then, which was beautiful. You don’t want to see them in a raggedy old photograph. So we wanted to do justice to them and once you start doing one, you have to do all of them.

From happening to find someone who was working to rebuild this enormous recording machine with no existing example or instructions to tracking down the descendants of these musicians, were there elements of the project that made you feel you were destined to tell these stories?

BM: I definitely did feel like we were being guided at times… Because once you find someone in a 1930 census, it’s a huge amount of work to track down their children. For one of the stories in the second film, I was looking at four or five of the first gospel performers to record and many of them had amazing stories. But there was this one song that I loved called “My Heart Keeps Singing” and it had this Caribbean feel to it…. But the only thing that is know is that it is recorded by Elder J. E. Burch and Congregation. So I went to the basement of the New York archive of Sony Records, and they’ve kept a lot of the recording sheets for Victor, what would become RCA Victor. And these are the sheets that an engineer at the day’s recording just type up saying “Elvis Presley today recorded “Hound Dog,” take one, take two, take three.” And I found the sheet for this Elder Burch recording. It just said the recording was in Atlanta and this is the session including “My Heart Keeps Singing” and just in the corner was written “Cheraw.” And I thought, maybe that’s a place…. So I went to Cheraw, South Carolina, and we started asking around with the town historians and no one had heard of Elder Burch. We were eventually pointed to an African-American, elderly man and we went to see him. He said, “Oh my God, I haven’t heard Elder Burch’s name since 1940. He has this church here, and I used to sneak in there as a kid and their music was incredible.” In fact the music was so amazing that the whole town, including white people, would sit in cars around this little wooden church with the windows down listening to this music. And then he said you ought to talk to my friend Ernest, he also used to go to that church, he’s in his eighties too. So I go to see Ernest and he says, “Oh my god you wouldn’t believe the sounds. I used to sneak into that church.” He was stunned that we had turned up and didn’t know that Burch had made records. He said that the person who was most influenced by Burch’s music who lived two or three doors up – Dizzy Gillespie! And he brought out this memoir of Dizzy’s [where he said], “Every Sunday I used to sneak down to Elder Burch’s church. I know everything I know about music, rhythm, melody and spiritual transport – it’s my soul inspiration for making music.”…. Dizzy Gillespie was probably one of the most important music ambassadors of the 20th century and that was all from Elder Burch.

There’s a beautiful symmetry between a film that covers how innovation, collaboration and diversity let America hear itself for the first time, and then a broadcast on PBS which holds those same ideals. Why did you choose to partner with PBS?

AM: First of all we didn’t go to any other broadcaster. We went to PBS and only PBS because this program, this body of work is about the people and [we wanted] everybody in this country that the film is about to be able to see it. If we went to HBO, Netflix, Amazon or Showtime they probably would have given us more money, but when you go to places like Shreveport, Louisiana and out into the wilderness those people do not have cable. So we wanted to make sure that everybody that this was about could see it. So that’s why PBS was our choice.

BM: This is a program for the people, by the people and it needs to be available to everyone. We looked at the subjects, particularly the poorer subjects of the film, and we thought they have to be able to watch this. It’s for them. So that was ideal option and on top of that what is public television if it’s not for this? This is what it PBS was designed for.

What are your ultimate goals and hopes for American Epic? What do you hope the impact of this work will be?

AM: T Bone Burnett always says, ‘Music is to America as wine is to France.’ And I’ve always said that music is America’s great cultural gift to the world. I’ve worked all over the world and wherever you go people love American music, and let’s remember what is so wonderful about America is its music and its technology.

BM: And its innovation and its entrepreneurism…. The fact Elmer Raguse is now an unknown figure – he is one of the fundamental guys that invented this machine, everything comes from that, and he should be remembered…. I guess my message in terms of art and performance is, particularly with music, the moment is really crucial, and capturing that moment…. It has an energy and at that time they called it “Lightning in a bottle.”

“American Epic” airs Tuesdays May 16 to May 30 at 8 p.m. on KCPT.

McGourty and MacMahon came to Lawrence, Kansas, to screen part of American Epic at the Free State Festival last summer. See a video excerpt from their panel discussion after the screening here. After the event KCPT talked with them about their filmmaking odyssey. Their responses have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

American Epic goes so far beyond a documentary series. The body of work that you’re creating also includes a book, contemporary recording sessions and a digital archive with the research and restored materials. What do call what you’ve created since it’s so far beyond just filmmaking?

BM: I think that’s why it’s called American Epic. (Laughs) Because once we started getting into the meat of the production, we realized it extended into so many other areas. And I think there’s a duty if you find this material to preserve it and protect. And to also preserve all the other stories you don’t have the opportunity to tell to make sure they’re documented and that that material is archived properly… There was almost like a football league table approach in how the 100 artists were chosen to make 10 [that are featured in the series.] But we realized early on that this material was really valuable even if this particular artist wasn’t going to make it into the film. Their interviews, the family’s interviews, the photographs those should be available. So that’s where the box set comes in with the hundred songs on it, because that’s like a cue for people to explore the thousands of things that are out there from that era.

AM: It was really to do justice to the people themselves and the families, because for example when we found photos of Mississippi John Hurt or [the Tejano musician] Lydia Mendoza you want the public now to see them as they were then, which was beautiful. You don’t want to see them in a raggedy old photograph. So we wanted to do justice to them and once you start doing one, you have to do all of them.

From happening to find someone who was working to rebuild this enormous recording machine with no existing example or instructions to tracking down the descendants of these musicians, were there elements of the project that made you feel you were destined to tell these stories?

BM: I definitely did feel like we were being guided at times… Because once you find someone in a 1930 census, it’s a huge amount of work to track down their children. For one of the stories in the second film, I was looking at four or five of the first gospel performers to record and many of them had amazing stories. But there was this one song that I loved called “My Heart Keeps Singing” and it had this Caribbean feel to it…. But the only thing that is know is that it is recorded by Elder J. E. Burch and Congregation. So I went to the basement of the New York archive of Sony Records, and they’ve kept a lot of the recording sheets for Victor, what would become RCA Victor. And these are the sheets that an engineer at the day’s recording just type up saying “Elvis Presley today recorded “Hound Dog,” take one, take two, take three.” And I found the sheet for this Elder Burch recording. It just said the recording was in Atlanta and this is the session including “My Heart Keeps Singing” and just in the corner was written “Cheraw.” And I thought, maybe that’s a place…. So I went to Cheraw, South Carolina, and we started asking around with the town historians and no one had heard of Elder Burch. We were eventually pointed to an African-American, elderly man and we went to see him. He said, “Oh my God, I haven’t heard Elder Burch’s name since 1940. He has this church here, and I used to sneak in there as a kid and their music was incredible.” In fact the music was so amazing that the whole town, including white people, would sit in cars around this little wooden church with the windows down listening to this music. And then he said you ought to talk to my friend Ernest, he also used to go to that church, he’s in his eighties too. So I go to see Ernest and he says, “Oh my god you wouldn’t believe the sounds. I used to sneak into that church.” He was stunned that we had turned up and didn’t know that Burch had made records. He said that the person who was most influenced by Burch’s music who lived two or three doors up – Dizzy Gillespie! And he brought out this memoir of Dizzy’s [where he said], “Every Sunday I used to sneak down to Elder Burch’s church. I know everything I know about music, rhythm, melody and spiritual transport – it’s my soul inspiration for making music.”…. Dizzy Gillespie was probably one of the most important music ambassadors of the 20th century and that was all from Elder Burch.

There’s a beautiful symmetry between a film that covers how innovation, collaboration and diversity let America hear itself for the first time, and then a broadcast on PBS which holds those same ideals. Why did you choose to partner with PBS?

AM: First of all we didn’t go to any other broadcaster. We went to PBS and only PBS because this program, this body of work is about the people and [we wanted] everybody in this country that the film is about to be able to see it. If we went to HBO, Netflix, Amazon or Showtime they probably would have given us more money, but when you go to places like Shreveport, Louisiana and out into the wilderness those people do not have cable. So we wanted to make sure that everybody that this was about could see it. So that’s why PBS was our choice.

BM: This is a program for the people, by the people and it needs to be available to everyone. We looked at the subjects, particularly the poorer subjects of the film, and we thought they have to be able to watch this. It’s for them. So that was ideal option and on top of that what is public television if it’s not for this? This is what it PBS was designed for.

What are your ultimate goals and hopes for American Epic? What do you hope the impact of this work will be?

AM: T Bone Burnett always says, ‘Music is to America as wine is to France.’ And I’ve always said that music is America’s great cultural gift to the world. I’ve worked all over the world and wherever you go people love American music, and let’s remember what is so wonderful about America is its music and its technology.

BM: And its innovation and its entrepreneurism…. The fact Elmer Raguse is now an unknown figure – he is one of the fundamental guys that invented this machine, everything comes from that, and he should be remembered…. I guess my message in terms of art and performance is, particularly with music, the moment is really crucial, and capturing that moment…. It has an energy and at that time they called it “Lightning in a bottle.”

“American Epic” airs Tuesdays May 16 to May 30 at 8 p.m. on KCPT.